Extremely Subjective and Somewhat Stream-of-Consciousness Thoughts on the Portrayal of Female Power and Sexuality in Othello

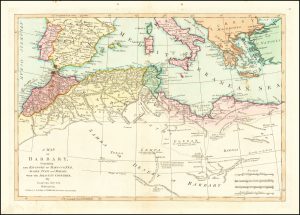

Although this map dates to the early 1800’s, it still presents across the top of the map of Africa from left to right in pink, yellow, green, and pink again the territories of Morocco, Algiers, Tunis, and Tripoli, all under the heading of Barbary.

Jessica Burr

Artistic Director

Blessed Unrest Theatre Company

These are merely my meandering imaginings around who these people might be. To begin with, the text of Othello is itself untrustworthy, historically and temporally inaccurate if not impossible. And there are assumptions made, for example we imagine that Barbary is of African origin because of her name, but there is nothing explicitly written about that. Nor is it stated that Desdemona’s mother is dead, although it is commonly accepted.

Desdemona, Emilia, Bianca. I’m interested in putting these three women next to each other on stage, as their backstories (as I interpret them), and experiences of power and sexuality vary so greatly. They form a tryptic of sorts. A portrayal of Woman as processed through the sensibilities of an Elizabethan man. Only three women appear on stage in Othello, be they represented by actual contemporary women or young Elizabethan men. At first glance we have The Virgin, The Mother, The Whore, and The Shadow. Wait… that’s not a tryptic. And if you go on to include the three deceased mother figures it’s a hexagon.

DESDEMONA

Desdemona, a virgin, though perhaps only for the first few minutes of the play. Her name, Greek in origin, implies any number of meanings including, “misery”, “ill-fated one” and “afraid of God”[1]. The demon, albeit an unlikely one. A demon by her own devices. A demon by virtue of having made choices for herself that push against any “values” that may have been bestowed upon her by either family or society. Has she lived as sheltered a life as I imagine? Her body untouched by violence or unwelcome caresses? Has no perverse, eccentric friend of her fathers after one too many goblets of valpolicella groped her under a majestic dining table? No errant servant stolen glances of her private ablutions through a peephole to render her shaky, ashamed and with no one in which to confide? I imagine her delicate infant self cradled by her mother’s African “maid”, wet nurses, nannies and even on occasion her once-mentioned, though we imagine now deceased, mother. And I wonder, when was the first time her feet were allowed to touch the ground?

As she grew, I picture her long (blond?) hair being brushed out indulgently every night, her (slender?) body bathed, perfumed, then carefully clothed by a girl perhaps little older than she. I like to think that no shame is conveyed in these gestures. Perhaps she even enjoyed the baths, the pleasure of being washed carefully by another with no thought as to why it was enjoyable. Later, she is praised for her beauty, and educated by thoughtful scholars, private tutors, not nuns who would have instilled terrors of sins of flesh. Desdemona’s education embodies all things beautiful, studying famous works of art first-hand, music, dancing, languages. I even imagine mathematics being used to explain concepts of beauty underlying the works of Da Vinci and the perfection of seashells. I wonder if learning took the place of what would later become in her a kind of dissatisfaction, and the driving force that leads her to take the violent action of breaking with her own culture.

She is kept close to her father, his “jewel”[2]. Maybe kept too close, stifled by the attention and privilege that surrounded her, and yet she did not escape to one of her many suitors. In fact, her only potential flaw is that that she rejected each of them. Until, seduced by the exotic stories told by a powerful General with a sexy accent, she elopes with him and sets off to live in occupied territory and war zone with her Love. Oh, and he’s Black.

Our early encounters with Desdemona are from the mouths of other people. She is first described, along with her new husband, as an animal.

Even now, now, very now, an old black ram

Is tupping your white ewe![3]

This wedding night description evokes more an act of animal husbandry than any kind of hot, consensual human sex, and is later described as “making the beast with two backs.”[4]

To call this a crude introduction is an understatement. On the other hand, Desdemona’s voice (as opposed to the vessel of her body) is introduced by the newlywed Othello, as he explains to the senate how she ostensibly instructed another man to woo her.

…yet she wish’d

That heaven had made her such a man. She thank’d me,

And bade me, if I had a friend that loved her,

I should but teach him how to tell my story

And that would woo her.[5]

What a way to find a voice! Thirdhand. I hear her inner monologue pleading in code. “Please tell this more suitable suitor to speak to me the way that You do, to relate interesting stories of adventure and foreign places. Tell him to look at me the way You look at me. Directly, taking me in completely, seeing through even the façade of loveliness that I have constructed for You. I mean, for him. To give him pleasure. Please tell him to see through that into who I really am. The way that You do. Please tell him to move me, to be authentic with me, and to not tolerate any presentation of myself to him that is not entirely genuine.”

How does Othello look at Desdemona? Does he take in the quality of her movements, the placement of her gaze? Is his own gaze polite and static? Or does his past and status allow him more leeway than that? Occasionally covertly glancing below the neck, or allowing himself to admire the shape of her wrists, the rhythm of her gait? Does Othello ever use an objectifying gaze, aggressive and hungry? And does Desdemona feel the thrill of his eyes upon her without knowing why she can suddenly feel every inch of her skin?

But I digress… A woman able to articulate what she wants. Imagine. No wonder people hate her! Does this ability to voice her desires combined with a lack of learned shame translate into an extraordinary sex life? Does she perhaps like sex more than she really “ought” to? Does this contribute to her husband’s behavior? Does Othello, while enjoying the fruits of Desdemona’s exploration without inhibition, also harbor a fear of being somehow inadequate, unable to satisfy all of her budding lusts? Does he watch her watching others and wonder what she’s thinking?

I try to imagine what it is like to experience a desirous touch for the first time from inside a body untainted by having needed to protect itself. I fantasize about this kind of absolute purity. I think it’s assumed that most young people experience the first stirrings of sexuality from this place but wonder how rare this opportunity really is. Too often I find Desdemona has been given short shrift, and is portrayed as whiny, self-absorbed and deluded. Is that because so many of the rest of us come from places sullied by mistreatment, by years of therapy to undo the unromantic and unwanted experiences that have forged us? Are we merely envious? I long for her to be genuine, to be given the autonomy to experience her own story truthfully and completely. We all know how her narrative ends, and if she’s portrayed as a dimwit, it’s all too easy to see the graceless unraveling from a mile away. If she is a loving and multi-dimensioned human being however, how much more complex and powerful could her story become?

MOTHERHOOD & SHADOW

There are no mothers in Othello. Or are there? Both Desdemona and Othello speak of their mothers. She to illustrate her newly acquired independence from her father, and he in relation to the gift of the handkerchief. Desdemona says almost tenderly to her father —

But here’s my husband:

And so much duty as my mother show’d

To you, preferring you before her father,

So much I challenge that I may profess

Due to (the Moor) this man my lord.[6]

There is a gentleness to Desdemona’s invocation, while she is quite possibly aware that the very mention of her mother cuts through her dad like a knife. I wonder what the arrow is that kills Brabantio so quickly…

By contrast, Othello’s mother is invoked as almost a threat.

That handkerchief

Did an Egyptian to my mother give;

She was a charmer, and could almost read

The thoughts of people. She told her, while she kept it

‘Twould make her amiable and subdue my father

Entirely to her love; but if she lost it

Or made a gift of it, my father’s eye

Should hold her loathed and his spirits should hunt

After new fancies. She, dying, gave it me

And bid me, when my fate would have me wive,

To give it her. I did so, and take heed on’t!

Make it a darling like your precious eye!

To lose’t or give’t away were such perdition

As nothing else could match.[7]

The Egyptian “charmer” and Othello’s mother seems to have merged into a spirit woman who is looking to defend her son at all costs, and who will not let the simple fact of being long dead stand in her way. There is a fierceness to her love that I imagine Othello is trying to invoke in Desdemona for himself. Perhaps his wife’s soothing ministrations are not enough. Perhaps a “fair warrior”[8] is not what he needs, but someone who can support him with a ferocity that she has no reference for. Perhaps this is where they begin to get lost in each other’s translations.

But does she not have a reference, or does the presence of Barbary illustrate an element of Desdemona’s life and understanding that cannot be contained within the confines of Venetian gentility? Motherhood and sexuality are rarely placed side by side, but that’s both absurd and unrealistic. Their entanglement makes people uncomfortable, but that is where they live, coexisting. In Othello, Desdemona’s mother, by virtue of how little we know about her, is kept in a petrified state of eternal purity to which her daughter really ought to be aspiring. Her African “maid,” on the other hand, is free to embody all the passion, ugliness and tragedy that comes with actually being human, that comes with having loved deeply, and with having lost her Love. We don’t know if Desdemona’s mother was ever allowed to love deeply. perhaps she experienced the massive wave of warmth, understanding, bewilderment and selfless adoration that can come with having a child just before her last exhale. I hope so. I would like to give her that. I’m hard pressed to imagine Brabantio as anything more than posturing and threatened when it comes to his interactions with women. This father, after all, wishes his daughter to have been “had”[9] by the ludicrous and violent (but lily white) Roderigo, rather than to have her explore the pleasures of touch and sex with the man that she loves.

BARBARY

Part of the family! (albeit imported). At what age was she taken from her warm place and rudely transported to the narrow and bone-chillingly damp streets of Venice? Old enough to have experienced both love and heartbreak. Did she have nothing to lose long before she arrived at Brabantio’s door via gondola at dusk? A completely foreign landscape, operating by water and lit by fire. No solid ground. Had thoughts of death already occurred to her? Did she arrive heavy with both heartbreak and having recently given birth? Why was it she who was brought in? Was she conveniently lactating? Had her own infant, the issue of her lost Love, been untimely ripped from her breast so she could serve wealthy Venetians and keep their children from certain death? Had Brabantio paid extra for this feature? Was Desdemona thrust hurriedly into Barbary’s arms in an attempt to save the infant’s life? Was there some relief in having breasts painfully engorged with milk finally suckled hungrily? Engorgement is a sensation of having razors in your chest. When it strikes it will drive a woman to do almost anything for relief, and when that finally comes it’s a sensation of such extreme gratitude that it could conceivably be construed as love for the person who takes it away. Was that their first encounter? Each feeling the profound release of abatement of pain and hunger, respectively?  The literal release of oxytocin the “happy hormone” produced with breastfeeding? Even with the detestable power structure, even when accompanied by the disgust of being held hostage to support the life of the offspring of her “owner,” I cannot imagine that this shared experience did not generate some kind of bond. Even against will. A Stockholm Syndrome of sorts… No wonder Desdemona thought they were friends, if indeed she did.

The literal release of oxytocin the “happy hormone” produced with breastfeeding? Even with the detestable power structure, even when accompanied by the disgust of being held hostage to support the life of the offspring of her “owner,” I cannot imagine that this shared experience did not generate some kind of bond. Even against will. A Stockholm Syndrome of sorts… No wonder Desdemona thought they were friends, if indeed she did.

As Desdemona grew, did Barbary try braiding her hair in the same manner that she braided her own? Just for fun? I wonder how Brabantio responded to that. I’ll bet it only happened once… But with nothing to lose, did Barbary whisper to the child in her native tongue? Was she able to see the confines of Desdemona’s own plight even inside of privilege and offer her incantations of strength and courage that would have been unknown to anyone else Venetian? While Desdemona’s education was outwardly centered around a Western idea of beauty, perhaps she was also exposed to something more complex, something so nebulous and powerful that not even she had words to describe later in life. By the time we learn of Barbary’s presence, it’s quite late in the game. She is invoked like a shadow, or an echo of something foreshadowed. As though a part of Desdemona’s unconscious has risen to the surface and must now be summoned in order to understand what is about to happen. We know that Barbary sang to Desdemona, a song of her Love who went mad and forsook her. Barbary sang that song on her deathbed. How long did she survive in Venice before she died? How did her death affect her young charge, and how old was Desdemona when she lost the woman whom she conjures just before her own death?

EMILIA

The first mention of Emilia, whose name implies ambition, to strive, excel or rival[10] (all rather powerful verbs to be attributed to a woman…), is of her lips and tongue. Emilia’s first entrance is accompanied by Desdemona lamenting, “Alas, she has no speech”[11].

Was Emilia born one of many children? Which one was she? Was eating competitive at her family table by virtue of occurring too infrequently? Was she an older sibling tasked with looking after younger ones, and therefore pushing food that should have been hers into younger mouths? Out of guilt? Perhaps to shut them up because the rumblings of her own stomach were still quieter than the whining of small children. Did this behavior predispose her to a kind of selflessness in order to preserve her own wellbeing? Did this “selflessness” help prepare her for a life with Iago? Or was she born too late to be handed food at the meager table and so married, or as good as sold, off at an early age? Far too early…

How has Emilia experienced touch? I tremble to think of what cold nights in a bed full of child-bodies was like once the candle was extinguished. Whose hands were where? Little hands that automatically grasp for breasts in search of comfort? Did she have older brothers who were starved for affection? Who had not yet learned their own physical boundaries, let alone hers? Who would eventually learn their own, but not hers because they would never need to? For her sake, I hope not.

Good thing she was pretty… Perhaps that allowed her escape. Or maybe she just exchanged one hell for another. Did her new husband make any attempts to woo her? Or she him? Was there ever a spark, a good feeling between them either between the sheets or in collusion to achieve a common goal? I wonder if she ever felt seen, heard, touched by her partner, or merely used. I wonder if Emilia has had lovers. I hope she has. I would like to give her the experience of being truly desired for simply being who she is. Of someone wanting to scale her walls with a real curiosity as to who was inside, and to give her pleasure (furtively, like candy held on the tongue and dissolved in secret). But that is not in my power. I can suggest it, but perhaps that’s too forgiving. Perhaps she doesn’t have the tools of a woman who has been adored, but merely those of one who has tried to conjure what that means in her own imagination. Or has she?

I like to imagine that Emilia looked up once and saw Othello, one side of his handsome face illuminated by a setting sun and gasped at his beauty and quiet power. That she inhaled a breath of longing just before it could be squelched by disgust, fear, and all that she had been taught about how the world works. I’m giving myself away as a romantic, but how can I truly empathize with these people and help an actor create a whole human being if not by processing them through my own visions, romantic or otherwise?

When Othello strikes Desdemona, Emilia knows what that is. She knows what that feels like, and perhaps even experiences it in her own body as if for the first time. A dam breaks in that moment, and something profound changes for Emilia. I think this is the instant in which she’s shaken into taking a more active role in her own journey. If we allow her that experience of vulnerable and compassionate humanity, and then later the taking of action even when it costs her life, imagine how complex and powerful her story could be.

It is details like these that make theatre that has the ability to change people. Events where characters do not adhere to a prescribed set of beliefs about them ossified over four hundred years of careful scholarship, but when they do precisely what they would not do. When they illustrate for the rest of us the human being’s ability to change, and to effect change. These are the moments I live for…

BIANCA

Bianca, whose name at first glance means white or fair in Italian, is also a shortened form of the word, Biancalani, meaning literally white wool and which is also the occupational name for a fuller[12]. Fullers were responsible for a step in woolen clothmaking which removed impurities that resulted in a smooth, water repellent fabric. In fulling, the cloth was first pounded with a wooded club or the fuller’s feet and hands, while often being ankle-deep in tubs of stale human urine which provided the necessary addition of ammonium salts and assisted in the whitening of the cloth. I include this detail simply because I find the sensory invocations of this process utterly inescapable. To be fair, it’s clear that the Romans used urine to serve this purpose but not necessarily the Elizabethans. And Bianca, while described as a seamstress is not pointedly referenced as a fuller, but I find it interesting that she might be engaged in this type of processing of fabric that is distinctly divergent from “Othello’s black handkerchief”[13] that Ian Smith describes as dyed in mummy (i.e., often bitumen procured from the bodies of corpses, and in this case as Othello states, “Conserved of maidens’ hearts.”[14]) in order to turn it a dark brown or black. In the larger arc of Othello, the fulling reference is also a harkening back to the first mention of Desdemona as a “white ewe”[15].

I have heard it said that Desdemona is “blackened” in Othello by the mere fact of being with Othello. How is it that the woman in the play who is most frequently portrayed as a prostitute is the one employed in the whitening of fabric? Has she surreptitiously been given a higher status than our heroine, despite the fact that she’s the one character who freely expresses an absolutely neurotic sense of jealousy? Bianca deals in time and accusation, and her subtext in my head is very clear…

“Where the hell have you been? I’ve missed you, baby. Where’d you get this handkerchief? Please come to dinner. Who gave this to you? Tonight. What woman? I’ll cook for you. Please. I’ll do anything. Now. Who have you been with? Right now. Are you cheating on me? I’m leaving. You’re cheating on me! Please don’t leave me. Come home with me. Now. Right now. Please, baby…”

Bianca has some sort of a sexual relationship with Cassio and is otherwise unattached. She makes her own living, and that’s pretty much all we know about her. Except her reputation for making trouble. Cassio avoids her in public. Why does she like Cassio so much? He treats her like crap. And if he’s so concerned with his Reputation, why is he carrying on with someone known for creating public spectacles? “She’ll rail in the street else.”[16] Says Cassio. They are an unlikely pair.

I imagine that growing up on Cyprus there was a kind of abundance so even the poor could thrive on fresh fish, wild figs, almonds and nectarines and sunlight. I imagine that Bianca didn’t know that she was poor until… until when? Did she choose not to marry? Or did she reject her suitors, finding none of them suitable, much like Desdemona?

Who taught her to sew and to full sheep’s wool? I like to think it was her grandmother (Giagiá, “grandmother” in Greek), a wizened old woman who also told her never to wed, but to construct a life over which she had agency at all costs. Giagiá spoke from experience. From a body exhausted by childbearing. From a lifetime with a husband who crafted too-strong wine and who was not kind. She also taught Bianca how to grow her own food and cook sumptuous meals for other people, men, when necessary. She knew her way around men, perhaps out of necessity, but she did not teach Bianca how to avoid the trappings of attachment or the cancer of jealousy. Bianca is suffering from the same disease that afflicts our hero and, in a way, it is her downfall as well. Jealousy, and lashing her affections to an unworthy man. I’ve seen that one before…

That said, I appreciate Bianca’s open expression of rage. Most women have learned to effectively suppress those inconvenient displays, and white women in particular are known to have higher occurrences of cancer than the rest of the population. I wonder why. Not to imply that Bianca is white. I think that, despite her name, it’s much more interesting to the narrative of Othello if she is a woman of color and therefore an Other. I also wonder how much Desdemona and Emilia could learn from Bianca’s audacity were they to allow themselves.

While the better part of Othello is marked by a deafening silence from the women, by the end all three have found their voices, for all the good it does them. Two of them are brutally murdered and one led off in shackles. The world itself has grown increasingly violent over the course of the play, and by the time Desdemona is asphyxiated. Strangled. Suffocated. Have we become so inured to violence that we remain unphased? Or worse, is it the run-of-the-mill violence-against-women-porn that we are so commonly exposed to and that give us a guilty secret thrill? Do our hearts break a little bit, even against our expectations? That is what I hope for. Heartbreak. And perhaps even a sense of having ourselves evaded responsibility, a sense of having just allowed something terrible to happen. Perhaps we will do better next time when we really are in a position to help or to stand up for another. Perhaps we’ll realize that we have a choice.

Alice Walker says that “breaking the heart opens it.”[17] As theatre-makers, heartbreak is one of the many sensibilities that we bring with purpose to the world, and there is a lot of heartbreak contained within the pages of Othello. It may feel uncomfortable or even unpleasant to you in the moment. But at least you are feeling. At least for that moment you are not numb. You are a little more alive than you were before, a little bit changed, and you can carry the experience forward with you as an understanding in your bones, as a strange salve to provide solace in the chaos of the world.

—Jessica Burr

[1] Meaning of the Name, https://www.meaningofthename.com/desdemona

[2] William Shakespeare, Othello, I.iii.195

[3] William Shakespeare, Othello, I.i.87-88

[4] William Shakespeare, Othello, I.i.115

[5] William Shakespeare, Othello, I.iii.163-7

[6] William Shakespeare, Othello, I.iii.184-9. “the Moor” has been changed to “this man” in the most current draft of the Untitled Othello script.

[7] William Shakespeare, Othello, III.iv.58-69

[8] William Shakespeare, Othello, II.i.179

[9] William Shakespeare, Othello, I.i.173

[10] Family Education, https://www.familyeducation.com/baby-names/name-meaning/emilia

[11] William Shakespeare, Othello, II.i.102

[12] Family Education, www.familyeducation.com/baby-names/name-meaning/bianca

[13] Ian Smith, Othello’s Black Handkerchief (Shakespeare Quarterly, Volume 64, Issue 1), Spring 2013

[14] William Shakespeare, Othello, III.iv.77

[15] William Shakespeare, Othello, I.i.88

[16] William Shakespeare, Othello, IV.i.160

[17] Alice Walker, The Temple of My Familiar (Harcourt Brace Jovanovich, 1989)